POV: DESIGNER. DIFFICULTY 2. LEVEL 1 – 1

POV: DESIGNER. DIFFICULTY 2. LEVEL 1 – 1

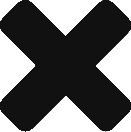

On May 21st 2010 Google cost the world $120 million. I remember it as the day I visited google.com and found a playable version of Pac-Man in place of Google’s logo. The doodle wasn’t any larger than the normal logo, but the faithful recreation of the sights, sounds, and gameplay of Pac-Man took me from yet another Google search to a glimpse into my past. Now, about five years later, Google has outdone itself with another Pac-Man project.

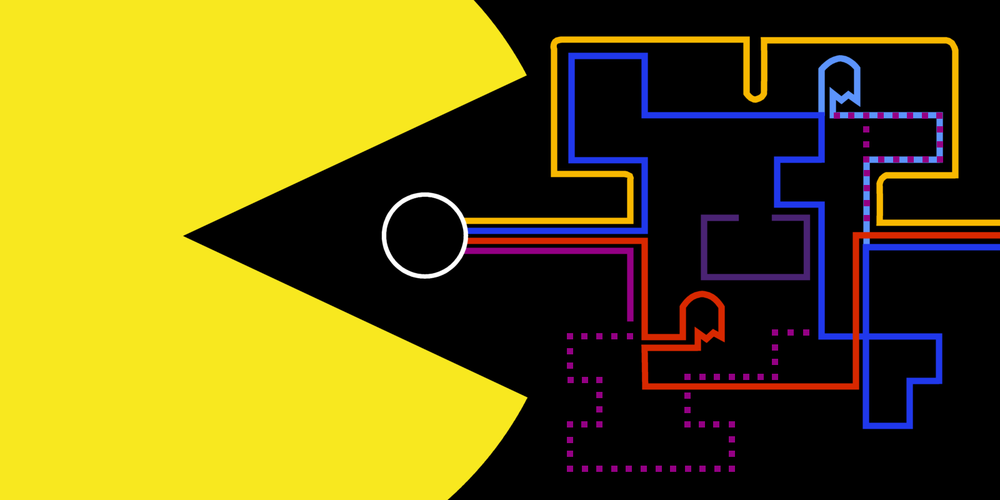

On April 1st, 2015, I got to play Pac-Man through the streets around my apartment, the DFW airport, and exotic locations around the world via Google’s April Fools’ Day promotion that created Pac-Man levels out of map data.

Between the original Arcade version of Pac-Man and the two Google Pac-Man projects, we have the perfect case study to examine the design of this classic. Because Pac-Man is a relatively simple game, we can dig deep into its entire design and highlight how the small differences between Google’s recreations and the original game make a big difference in the player experience. In this article, I’ll cover the basic mechanic of Pac-Man and build from there in future posts.

There is only one mechanic in Pac-Man; MOVE. No jumping, punching, or shooting. Just moving up, down, left, and right with no momentum or acceleration to worry about. In fact, You don’t even have to hold a particular direction since Pac-Man continues to move in the direction he’s going until stopped by a wall or a Ghost. What’s great about Pac-Man, and what creates gameplay of interesting choices, isn’t deciding how to move, but deciding where to move and when. Still, with controls so simple, there are a few subtle details in the tuning of Pac-Man’s MOVE mechanic we should cover.

In the original Pac-Man arcade, the entire game is designed to fit onto a grid. Pac-Man and the Ghosts are one square large. The walls and lanes are also mapped to this grid so that all movement through the maze is both clear in how it communicates travelable spaces, and clean in that there are no sprite edges to get hung up on as Pac-Man rounds corners.

To make movement even smoother, players can input the direction they want Pac-Man to move before Pac-Man reaches a turn. Doing so allows Pac-Man to turn the corner as quickly and efficiently as possible. This leaning into turns due to the buffered input helps reduce the skill needed to make efficient turns thus freeing up the player’s attention to focus on the strategy of surviving the maze.

The Google doodle nails the controls of Pac-Man. It’s free and you should play it right now to remind yourself how smooth controls lay the foundation for smooth gameplay. Treasure the finely tuned controls while you have them because the controls in the Google map Pac-Man are frustratingly bad.

The core creative conceit of Google Maps Pac-Man (GMPM) is obvious: play Pac-Man out on the roads of the world. The organic geometry of roads, with curves and many-way intersections at odd angles, significantly complicates the control design of Pac-Man.

There are two facets of controller design to focus on here: directness and intuitiveness. Controls are direct when mechanics (player actions) are designed in a way that matches the input method. For Pac-Man arcade version Pac-man can only ever move in a cardinal direction, and an arcade stick allows only cardinal directions, thus forming a perfect mapping. In other words, the player cannot manipulate the input in a way that can’t be reflected in the game. Pressing up moves Pac-Man up always. This design also makes the controls intuitive.

In GMPM, even the controls are not as direct or intuitive as the Pac-Man arcade version, and I blame the curves. When you press up on the Google Maps version, Pac-Man’s path can eventually curve so that Pac-Man moves left, right, down, or any angle in between. Pac-Man will keep traveling down even a curved path automatically. But it’s when I attempt to buy time by moving back and forth along a single curved road that the lack of directness becomes troublesome. On a curved road do I press left-right-left, up-right-up, or some combination of diagonals?

Diagonal road intersections are especially frustrating in GMPM. It’s hard to tell if you should press one or two directions to make a diagonal turn. Because the turns can branch off at any angle, even adding diagonals through 8-way movement controls won’t eliminate ambiguous turns. Since you often can’t tell where Pac-Man will go at an intersection if you hit a certain direction, playing Google Map Pac-Man becomes more about how to move instead of just when and where.

D-pads are the best input device for instantaneous movement at constant speeds and quick, repeatable discrete movements along 4 axes. Curved movement in games necessitates the use of more complex rules to govern movement that tend to benefit from more complex control input devices like analog sticks. Fortunately, the Google map Pac-Man offers mouse control. With a small yellow arrow indicating the direction Pac-Man will move if possible, the mouse helps players navigate curved paths and angled turns with greater accuracy than the digital arrow controls. Unfortunately, because the mouse is a relative pointing device, Pac-Man will attempt to move toward the mouse cursor at all times. This means you can’t simply move down roads by tapping a direction and taking your hand off the controls. If you aren’t constantly adjusting where the mouse points, Pac-Man may take turns or even reverse direction when unintended. The worst case of this is happens when Pac-Man moves off the edge of the screen–where he ends up is often asymmetrical to where he came from and unpredictable. Keeping control over Pac-Man via mouse position tends to require quick and precise mouse movements. During these brief moments, I feel like I’m playing a first person shooter, not a maze runner.

For the Google Map Pac-Man I like the arrow keys for their simplicity, but I end up using the mouse controls for their accuracy.

Controls and mechanics are the first step to understanding a game. In part 2, we’ll look at what makes Pac-Man gameplay so interesting

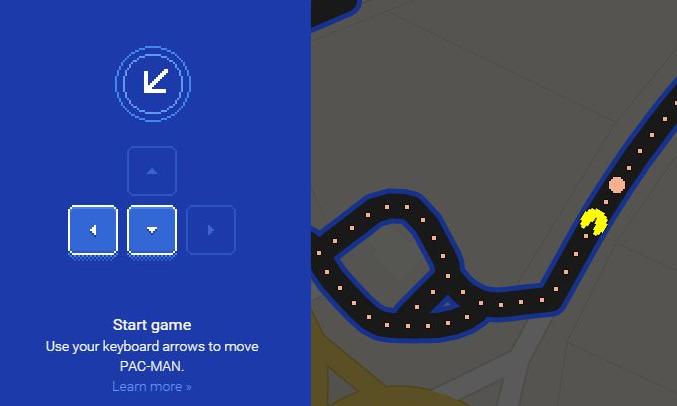

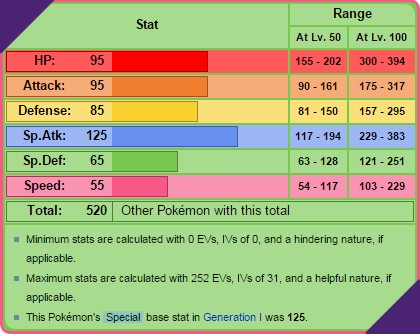

from bulbapedia Bulbagarden

from bulbapedia Bulbagarden FROM BULBAPEDIA BULBAGARDEN

FROM BULBAPEDIA BULBAGARDEN

image from jinx.com

image from jinx.com

POV: Designer. Difficulty 2. Level 1 – 1

POV: Designer. Difficulty 2. Level 1 – 1

taken from Randall’s XKCD.

taken from Randall’s XKCD.