POV: PLAYER. DIFFICULTY 3. LEVEL 2 – 1

POV: PLAYER. DIFFICULTY 3. LEVEL 2 – 1

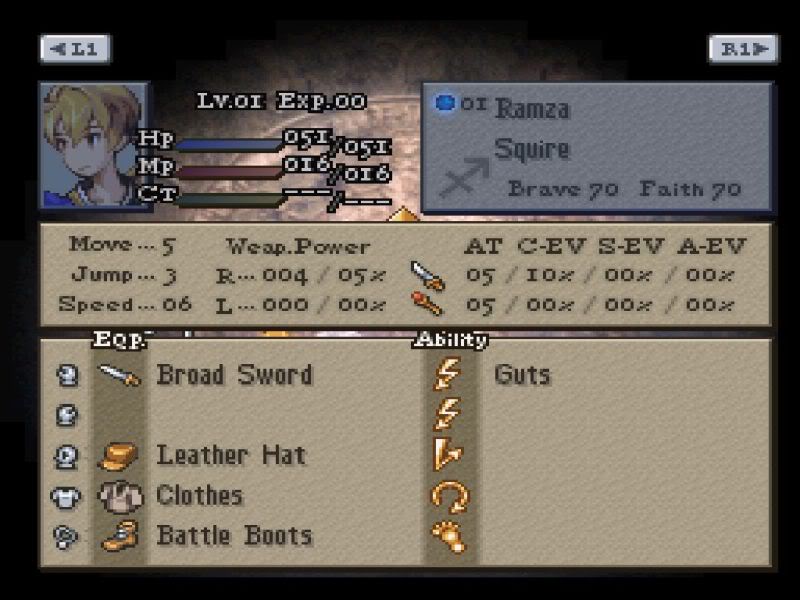

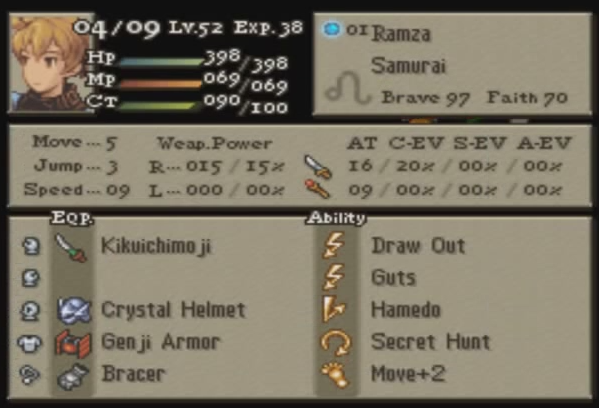

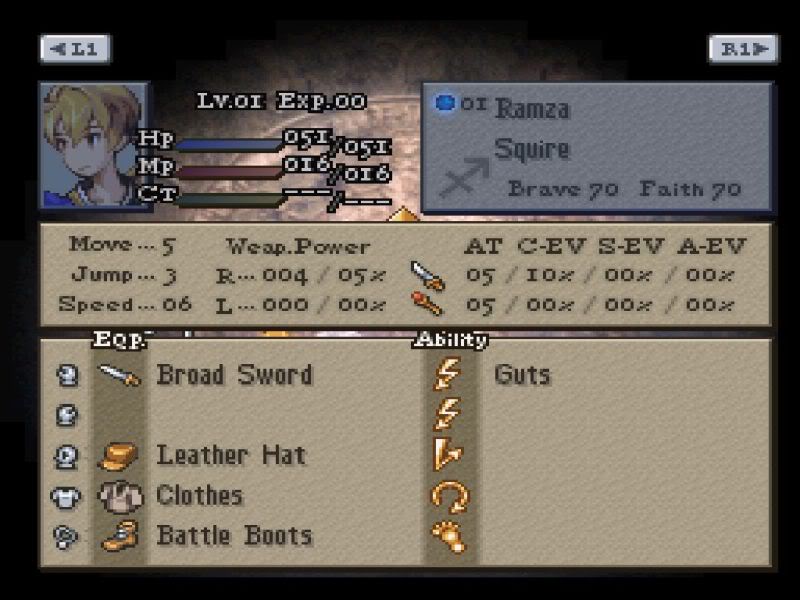

To get a full view of the systems design of Final Fantasy Tactics requires an examination of the many ways that characters, enemies, and maps vary. For this first article, let’s take a look at the composition of a character. We can start by taking a look at Ramza, the hero of Final Fantasy Tactics, at the very start of the game. Below is a screenshot of Ramza’s status screen in the first battle where the player has full control.

This screenshot shows most of the relevant attributes of a character–there are 34 in total spanning stats, equipment, and abilities. Analyzing these attributes, we can gain a handle on the design space of characters in the battles of Final Fantasy Tactics.

All battles have an objective of either killing a specific enemy unit, or killing all enemy units. Since reducing a character’s HP to zero is the most common way to kill it, HP earns a special place in the design space. All successful strategies have unit preservation (through minimizing HP damage) as a key consideration. Though the player can win battles through spending all of their effort dealing damage via attacks and abilities, many strategies also take advantage of powerful status-inflicting spells to temporarily hamper opponents, or take them out of the fight permanently (regardless of their HP total) by turning them into statues, frogs, or outright killing them by directly inflicting the “Dead” status.

I’ll cover the 33 different status effects in depth in a future article. For now let’s focus on what we can see on the status screen and understand the statistics that make up a character by taking a tour of combat.

The Basics of Combat

As a player of a turn-based game the first two questions that come to mind are “when do I take a turn?” and “what can I do on a turn?”

(From HCBailly’s Let’s Play. If the player were to select “Time Magic” or “Black Magic” here, a further submenu would open letting them choose the specific ability they’d like to use.)

(From HCBailly’s Let’s Play. If the player were to select “Time Magic” or “Black Magic” here, a further submenu would open letting them choose the specific ability they’d like to use.)

Final Fantasy Tactics has an interleaved turn system where the player gets to take a turn for each character in an order determined by the characters’ statistics. Characters go individually when they’re ready.

A character’s Speed stat determines how often they get to take a turn. On a character’s turn (called AT by the game) the player can have the character MOVE, ACT, or both, or neither. Choosing not to MOVE or ACT makes the character’s next turn comes faster.

A characters can MOVE at most a number of tiles equal to their Move stat, and any vertical distance between two tiles along the path of movement can’t be higher than their Jump stat.

When the player chooses to ACT with a character, they get to choose to Attack with their weapon or use an ability. Some of these abilities are resolved immediately, while others may take some time during which other characters may take further turns.

Abilities used offensively, i.e. to deal damage or inflict status effects, can be magical (like the Wizard’s spells), physical (like the Monk’s martial arts), or neither (like the Mediator’s talk skill). There are a number of different formulas to determine hit chance and damage for different abilities, but understanding if the ability is physical or magical keys you into what stats the game takes into account when doing the calculations.

Many abilities have a base 100% success rate, like physical abilities, but others have a success rate based on some formula involving the relevant attack stat (Physical Attack, Magical Attack, Speed, and Weapon Power, typically), some constant, and Zodiac compatibility. (I’ll be covering Zodiac-related rules in a future article.) After the die roll for success rate succeeds, then the ability is subject to the defender’s evasion depending on what kind of ability is being used and some other conditions.

Think of evasion as layers of defense. The attacker has to pass each layer by rolling a 100-sided die and getting a result higher than the defender’s evasion percentage. If any die rolls end up lower, the attack misses.

If a magic attack is used, the defender uses their Shield’s (“S-Ev”) and Accessory’s (“A-Ev”) magic evasion percentage to try to cause the attack to miss.

If an attack is physical, the process is slightly more complicated. Which evasion percentages apply to a given physical attack is based on the relative position of attacker and defender. If…

- the attacker is in front: all evasion stats apply;

- the attacker is to the side: shield, accessory, and weapon evasion apply;

- the attacker is to the rear: only accessory evasion applies.

If the attack passes all of these checks, it takes effect on the defender by dealing damage or applying a status or both. Damage formulas for the ATTACK action are based on the weapon involved and usually include some combination of Weapon Power (WP) and Magic Attack (MA), or Physical Attack (MA). Guns only rely on WP, squaring it to determine their damage, and there are a few weapons, as mentioned earlier, which use Brave as a part of their damage calculation.

Damage calculations for magical and other attacks typically depend on MA or PA and some constant factor. Magic attacks damage is additionally multiplied by the Faith of the caster and target as a percentage. I.e. Damage * (My faith / 100) * (Target Faith / 100).

Jobs

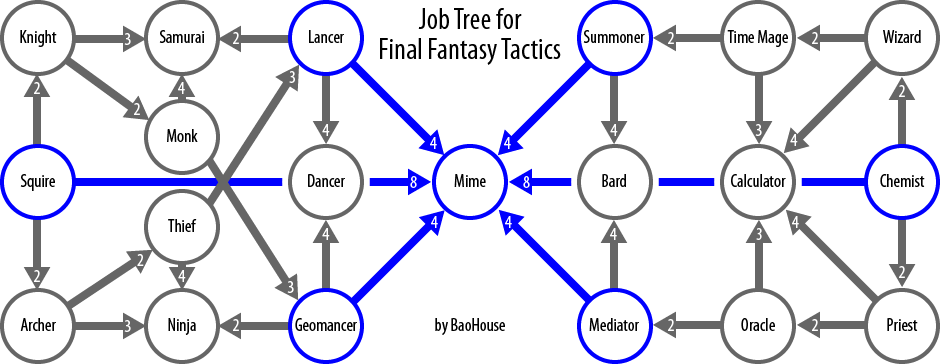

Final Fantasy Tactics has a relatively complicated battle system, where characters are throwing damage and status effects around to try to gain the upper hand–but how do they get these abilities? They get them through the Jobs they’ve had.

Jobs are akin to classes in most RPGs, but act a little differently than you might expect if you’re familiar with how classes tend to work games that borrow from Dungeons & Dragons.

The player can select one Job for each character, and change each character’s Job between battles. This Job determines the character’s stat growth when they level up and provides percentage bonuses to HP, MP, Speed, Physical Attack, and Magical Attack. For example, a Knight has more HP and Physical Attack, less MP and Magical Attack; a Wizard has lots of MP and Magical Attack, but not much HP and Physical Attack; a Ninja has great Speed, good Physical Attack, but low MP and middling other stats.

Each job has a base Move stat and Jump stat, as well. Ninjas are much more mobile than Knights not only because their Speed is higher, but also because they can Jump and Move one tile more.

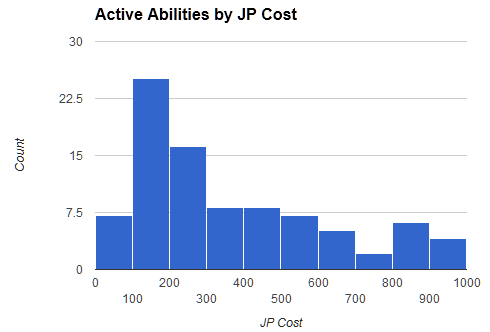

A character gets a group of abilities from their Job. Knights get “Battle Skill” abilities which let them break opponents’ equipment; Wizards get “Black Magic” abilities which let them deal elemental damage at range; Ninjas get “Throw” which lets them toss various items at enemies to damage them based on the item’s stats. Characters can use these abilities during the ACT part of their turn. But before a character can use such an ability, the player must unlock it for that character by paying its cost in Job Points (JP) between battles. Each character has a JP pool for each job. A character gains JP for a Job when they successfully ACT while they have that Job–abilities have to hit their target, friend or foe, for JP to be awarded.

The player can equip each character with an additional ability group from another Job, as well as the “automatic” ability group granted by the Job the character currently has. This secondary ability group can be used just the same as the ability group given by the character’s current Job.

Abilities

Abilities are what really bring the characters to life in battle–the abilities the player equips to his characters, and the abilities that appear on the various AI-controlled enemies, are the main source of variety in the battle system.

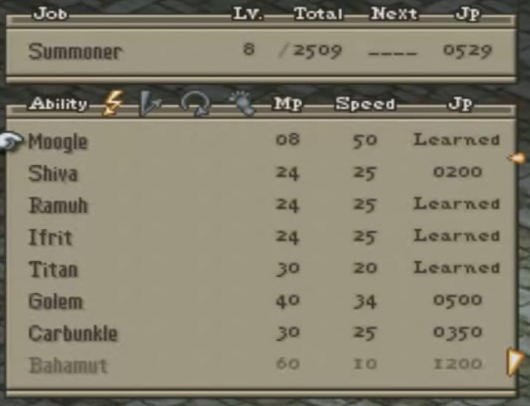

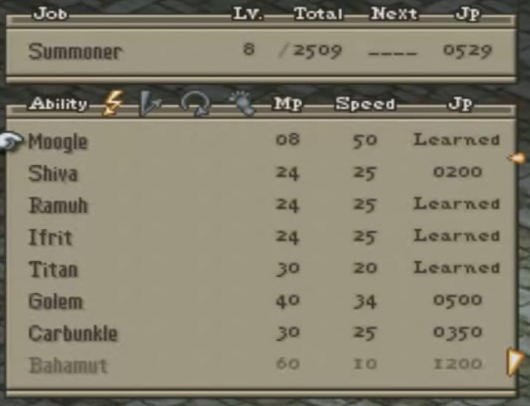

In addition to the two job ability groups mentioned above, the player can equip each character with one Reaction Ability, one Support Ability. and one Movement Ability. Below is a screenshot of the Summoner’s Active Ability set, known as “Summon Magic”.

(The Summoner’s Active ability set. From SnapWave’s Let’s Play.)

(The Summoner’s Active ability set. From SnapWave’s Let’s Play.)

Reaction abilities have a percentage chance of triggering their effect based on the character’s Brave stat when the character has certain kinds of abilities used on them. Reaction abilities give the character a chance to immediately react to being hit by, say, countering a spell with a spell of their own, or doing a physical attack in response to an enemy’s physical attack. Other reactions include increasing the character’s speed stat by 1, adding a positive status effect, and automatically using a potion to restore its health.

Support abilities are a motley assortment of passive abilities and a couple of active abilities. Examples: Increasing physical or magical attack power, granting the ability to throw curative items to nearby allies, and granting the ability to go into a defensive posture that doubles all evasion. Support abilities can also do much more unusual things, like unlocking more powerful abilities for nearby monsters, and “poaching” rare items off of monsters killed by this character.

Movement Abilities give the character some benefit each time they MOVE during their turn, or somehow enhance their MOVE action. Benefits can include finding hidden items, increasing the jump or move stat, ignoring height all together, or gaining HP, MP, JP, or XP after each MOVE action.

Equipment

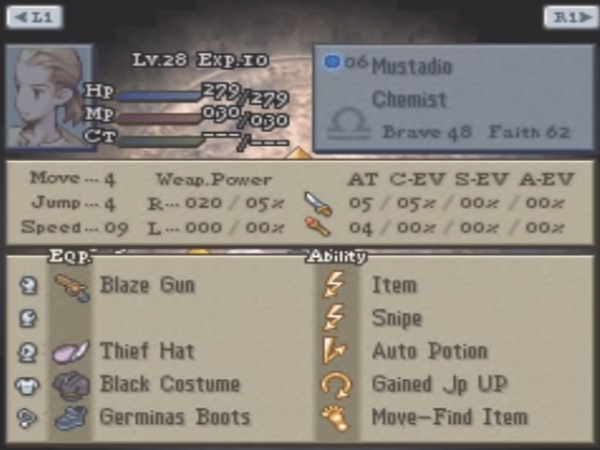

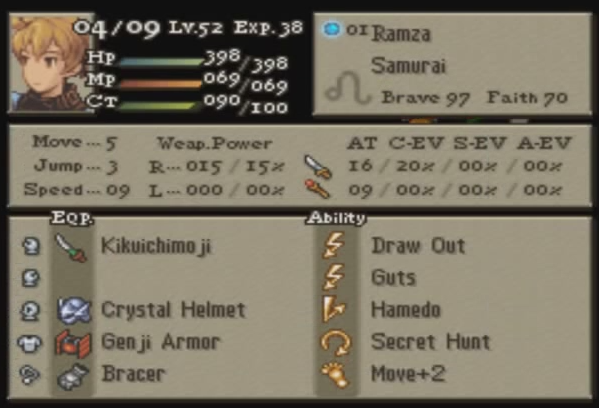

Below I’ve enumerated the stats and bonuses for the equipment on two late-game characters, so you can get a sense of what role equipment tends to play.

(From GetDaved!’s Let’s Play.)

(From GetDaved!’s Let’s Play.)

| Equipped Item |

Effect |

| Kikuichimoji |

15 Weapon Power, 15 Weapon Evasion |

| Crystal Helmet |

+120 HP |

| Genji Armor |

+150 HP |

| Bracer |

+3 Physical Attack |

This Ramza is configured to be able to absorb physical attacks. His high HP allows him to take the hits that his relatively high evasion doesn’t prevent outright. The Kukuichimoji sword allows Ramza to deal PA * Brave / 100 * WP damage, which in this case works out to 225 (This is lower than you would expect from the equation because the PSX doesn’t support floating-point math and will drop the remainder of PA * Brave / 100 before multiplying that result by WP.) Having the sword also allows Ramza to use a Job ability which deals MA * 16 = 144 damage to enemies in a line eight tiles long from either Ramza’s front, one of his sides, or rear.

The only way the player can increase the HP and MP of his characters, short of leveling them up or changing jobs to something tankier, is to equip them with different items. Typically body and head items provide the most HP and MP. Ramza, who is built as a melee combatant in the screenshot above, gets 270 of his 398 HP from his equipment. In this particular case, it’s clear how armor plays a large role in Ramza’s ability to absorb damage, since it accounts for two-thirds of his HP.

Ramza’s Job, Samurai, contributes 20% to his evasion rate (listed under “C-Ev”) while his katana contributes 15% (listed under “Weap.Power” after the slash), meaning an opponent physically attacking him from the front will only hit 68% of the time. Meanwhile, Ramza has no magical evasion whatsoever, so he’ll be quite vulnerable to magical attacks. He could put on an accessory, such as the Feather Mantle–the best such item in the game–which gives 30% magic evade and 40% physical evade, to improve his survivability against magical attacks. Remember that evasion granted by an accessory such as the Feather Mantle applies to attacks regardless of where they’re coming from–even if an enemy is attacking Ramza from behind he’ll get that 40% physical evasion!

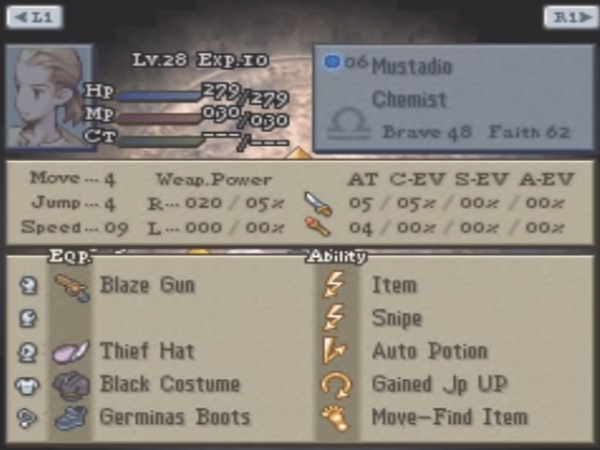

(From HCBailly’s Let’s Play)

(From HCBailly’s Let’s Play)

| Equipped Item |

Effect |

| Blaze Gun |

20 Weapon Power, 5 Weapon Evasion |

| Thief Hat |

+100 HP, +2 Speed, prevents Don’t Move and Don’t Act status effects. |

| Black Costume |

+100 HP, prevents Stop status effect. |

| Germinas Boots |

+1 Move, +1 Jump |

Mustadio, like Ramza, relies on equipment for a significant chunk of his HP–in fact, even more than Ramza–but Mustadio’s build has more of a focus on staying away from enemies and hitting them with his gun. Guns are unique among weapons in that their damage is entirely based on the gun’s Weapon Power and has nothing to do with the wielder’s Physical or Magical Attack stats. Guns also can strike from the longest distance of any weapon attack in the game, with a range of 3 to 8 tiles. In contrast, crossbows tend to have a range of 3 to 4 and longbows have a range of 3 to 5. Mustadio’s gun, the Blaze Gun, is a magical gun, which acts more like a magical attack in that its damage is proportional to the Faith of the caster and target–its effectiveness still has nothing to do with PA and MA stats, though! Another important, unique detail about guns is that they ignore evasion entirely. They typically do less raw damage in exchange for hitting more often. It’s a great way to counter evasion-rich characters like the Ramza we just took a look at.

To stay away from enemy combatants who can take advantage of Mustadio’s woeful evasion of 5% from his weapon and 5% from his class, Mustadio relies on both his modest Move and good Jump, as well as his equipment’s capacity to prevent the most common status effects that would pin him down: Don’t Move would hold him in place and Stop would prevent him from taking turns all together.

This is Just an Introduction

It took many words just to give you the basics of the way characters are designed in Final Fantasy Tactics, and there is still so much to talk about. Over the next month expect a number of articles breaking down in detail many of the design facets discussed here. Stay tuned!

POV: DESIGN. DIFFICULTY 3. LEVEL 3 – 1

POV: DESIGN. DIFFICULTY 3. LEVEL 3 – 1

(From The Final Fantasy Wiki)

(From The Final Fantasy Wiki)

(My Knight saves over 1,000 JP by inheriting a defeated Knight’s crystal.)

(My Knight saves over 1,000 JP by inheriting a defeated Knight’s crystal.)

POV: PLAYER. DIFFICULTY 3. LEVEL 2 – 1

POV: PLAYER. DIFFICULTY 3. LEVEL 2 – 1

(From HCBailly’s Let’s Play. If the player were to select “Time Magic” or “Black Magic” here, a further submenu would open letting them choose the specific ability they’d like to use.)

(From HCBailly’s Let’s Play. If the player were to select “Time Magic” or “Black Magic” here, a further submenu would open letting them choose the specific ability they’d like to use.) (The Summoner’s Active ability set. From SnapWave’s Let’s Play.)

(The Summoner’s Active ability set. From SnapWave’s Let’s Play.) (From GetDaved!’s Let’s Play.)

(From GetDaved!’s Let’s Play.)  (From HCBailly’s Let’s Play)

(From HCBailly’s Let’s Play)