POV: DESIGNER. DIFFICULTY 3. LEVEL 1-1

POV: DESIGNER. DIFFICULTY 3. LEVEL 1-1

Marcus Says: A great introductory piece to the world of game balance and a great example of how to deliver a message successfully without having to tease out, elaborate, source, and prove every detail. Which is something we note here at Design Oriented. Transitioning from Richard’s blog, Critical-Gaming, which featured a technical writing style to DO has been a learning process. Often times we feel as if we must tell the complete story on any topic least we sell the “truth” short. But as this article shows, there is a time for detail and there is a time for clarity. Some definitions in the article might seem a little inadequate to sticklers and some of the “tools for a better game” might seem a little too self-help-bookish for the people who have or are currently in the thick of game development. But who cares? That isn’t the point of the article. It’s meant to get your feet wet. There are links on the side where Sirlin goes into greater detail if that’s what you’re looking for.

Yomi is a great term for describing the Rock Paper Scissors competitive process. It’s punchy and able to be yelled in an energetic cry. It passes the cool-enough-to-be-an-anime-technique test. I can imagine a plucky young lad who hits a rough spot in his game of Rock-Paper-Scissors cry “YOMI!!! LEVEL 2!!” to power up and conquer his foe.

Mike Says: Balancing competitive games is one of the hardest things to do in game design. Sirlin’s take on the matter is informed by his own extensive practice and relative success in the field–he’s beyond qualified. But Sirlin’s definitions in the first and second page are unsatisfying to me because they often are delivered from a hindsight-rich perspective. I’m left with questions like: How does the fact that balanced games last years and years through competitive play inform my ability to judge and adjust balance now? Having a goal is great, but goals that can’t be judged for another five years are far less useful. Maybe they’re what we need, though, to keep our focus right, though I wonder who would design a hardcore competitive game and NOT want it to last a long time.

His advice to gauge your balancing efforts by categorizing asymmetrical factions/characters into tiers based on their current relative power, and encouraging the production of tier lists among playtesters, is great concrete advice. I’d like to see a lot more iteration on techniques for introducing the kinds of self-balancing systems he mentions into more genres of games, or identifying such properties of systems and getting a better grasp on them.

Sirlin’s reliance on intuition and deep understanding of the cognitive factors involved makes him highly qualified and effective as a designer, but the substance of the advice ends up being “playtest a lot and be careful, also get good at some game at some point” which is advice I’ve read just about everywhere in game design. The road to being a great game designer is incredibly long and arduous–the road to consciously understanding game design seems to extend into places far outside of where our feet have carried us.

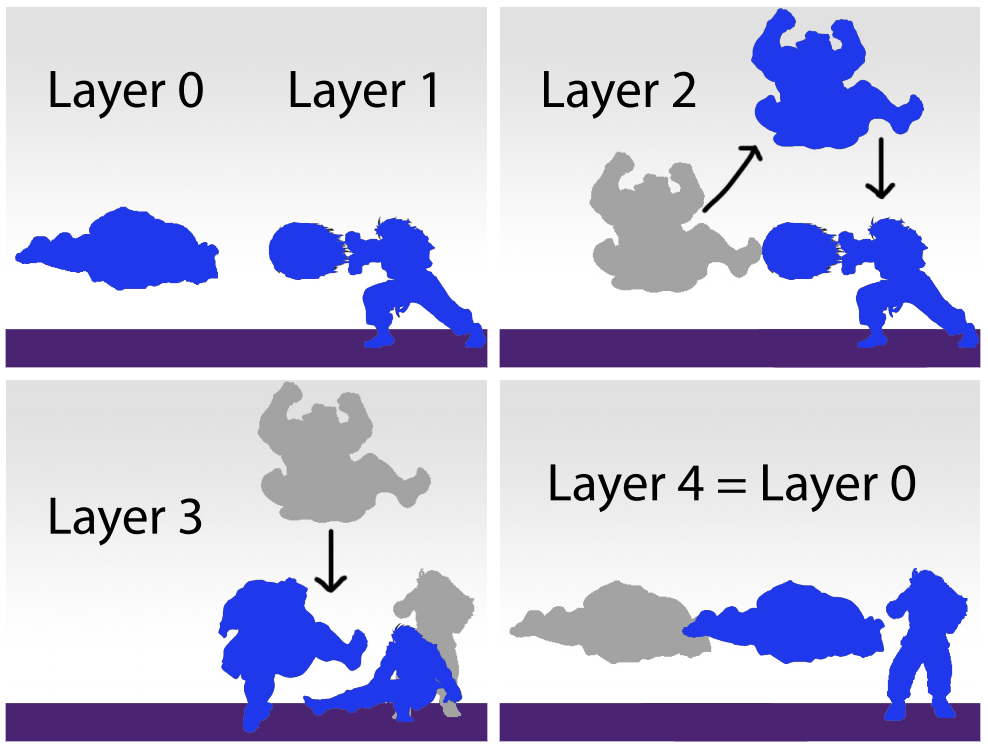

Richard Says: Those diagrams do a pretty great job of showing the different outcomes of a double blind game scenario. You probably have to have Street Fighter knowledge to understand though. It’s still one of the best documents out there that talks about balance. Years ago, this pdf sparked a lot of content on my old blog Critical-Gaming.