Sememster 3: Development

So you have an idea for a course? Great! That's the easy part. What makes level design such a complex art is going from idea to playable level and having it communicate the idea to the player. And if the player has fun and gets your idea all while playing, that's a double win. As of this writing, the Workshop has assembled over 400 unique gameplay ideas. Ideas are what make courses unique and memorable while appealing to complexities beyond pure gameplay challenge. The greater the capacity of a game to convey ideas, the more power and flexibility it has. Fortunately, Super Mario Maker 2 has unreachable potential.

Yes, I do think it's really important to decide on a core concept in level design. — Miyamoto

1. The Power of an Idea

Most of our gameplay ideas can result in dozens of different levels. Each idea is flexible and abstract. We are typically inspired by ideas, share ideas, and dream of ideas. Thinking about the nitty-gritty details is something that can wait until the level is actually being constructed.

2. Consider How To Present The Idea

It's possible to make your chosen gameplay idea the main focus of a level or make it more subtle like putting it in a secret area. The idea can be implemented in an exaggerated way or more smoothly incorporated into standard Mario level design and platforming challenges. It's your choice.

If a gameplay idea is presented as a single example, it's essentially a "one-off" implementation. This means the other areas or challenges in the level won't develop the one-off gameplay idea. Separate areas equal separate ideas.

The opposite of a one-off idea, is an idea that is developed across multiple sections of a level. A common type of development is taking the idea that's already in the level and adding a section with a similar set up but with a surprising twist. Players may think that they know what to expect and then their expectations are subverted. Developing a concept is more powerful than a one-off. It allows designers to build up player skills and expectations over time. Developing an idea may be necessary depending on how complex your idea is.

"This is something that Mr. Miyamoto talks about. He drew comics as a kid, and so he would always talk about how you have to think about, what is that denouement going to be? What is that third step? That ten [twist] that really surprises people. That's something that has always been very close to our philosophy of level design, is trying to think of that surprise." — Hayashida

Another common type of development is tutorializing the gameplay idea. This means introducing the concept in a less complex, less difficult, and less punishing way. This is not about dumbing the idea down. Stories introduce characters early so you know who they are and what they might do in the plot. Well formed arguments lay out definitions and simple ideas up front so the argument can manipulate them to convey more complex ideas. TV shows use establishing shots so scene changes are clear and the viewer knows the setting are even if it's deep inside an unfamiliar building. Music uses choruses and refrains to rehearse melodies. The main goal of all these art forms is to convey their ideas, ideas which generally trigger emotional responses from the audience. The more clear the conveyed idea, the stronger the emotional effect.

Well, I think it has a lot to do with the acquisition of a skill...So that's sort of what we try to do with the way people relate to gameplay concepts in a single level. We provide that concept, let them develop their skills, and then the third step is something of a doozy that throws them for a loop, and makes them think of using it in a way they haven't really before. And this is something that ends up giving the player a kind of narrative structure that they can relate to within a single level about how they're using a game mechanic. — Koizumi

3. The IDEA Directs Decisions

This is where the difficult to describe, nebulous aspect of creation comes into play. Having worked with music composition teachers, art teachers, and creative writing teachers I find it interesting that all of them had something similar to say about creativity. It turns out, they can't tell you what note to put where, how to draw your picture, or how to shape your sentences. There are dozens of ways to take on the next step in the creation process and hundreds of reasons for and against doing it. If they try to be too specific they'll ultimately be creating the work for you. The decisions have to come from you. And you'll be making a lot of them.

With design, you must have a reason for every decision you make. If you don't think you have a reason, then your reason is "whatever." If that's the case, your audience will likely think "whatever" as well. Design is much more than finding ideas that are cool. Design is more than anticipating which parts of your idea will work well together and which parts won't. The highest level of design pushes past these considerations to reach a point where solutions are made to the problems that naturally arise.

When you have a gameplay idea clear in your mind, your creative decisions will be focused. Your mind is the result of all your experiences, inspirations, practice, and dreams. You can't make a "random" creative decision. The options and choices that come to mind are really memories of options and choices you've experienced in the past. And these memories have emotions and history and other associated ideas attached to them. The human mind is a complex web of synaptic connections. Though the reason why you make a creative decision may be hard to articulate, keeping the gameplay idea in mind will help guide your decisions.

4. Your Idea is the Key to Decode Your Design

There is no formula for perfectly developing a gameplay idea. Ideas are abstract. This abstractness gives it a flexibility to be applied to a variety of different situations and expressed through a variety of mediums. This flexibility is the strength of an idea, and also what makes it impossible to pin down with a precise method.

Art is arbitrary, meaning it's highly reflective of an individual. Design is rule and solution oriented. This allows us to understand the quality of design in objective ways. For example, if a vacuum cleaner doesn't create suction, then it is functionally broken. This is not an opinion.

Many art forms are a combination of art and design. For this reason, it's very hard, possibly impossible, to reverse engineer "why" creators made their decisions just by looking at their works. Why is this ? block placed here in SMB 1-1? Why is this platform 5 blocks long instead of 4? The reason can be as understandable as needing to give the player an easy Super Mushroom. Or as arbitrary as it just felt right to make it 5 blocks long. Or as chaotic as " my hand slipped and I left it that way." Logical. Personal. Accidental. We cannot determine with certainly why an individual decision was made. But you, as a creator, should know who you are, what you're doing, and why.

5. Understand Your Design Space

To design better levels, having a detailed understanding of the course idea is best. The more you can break down the idea into many individual details, the more focused your decision making will be.

When creating characters in fiction writing, a common exercise is to develop a back story for their character. A writer might even figure out what's in the character's pockets or what they had for dinner last week. Even though these details may never make it into the story, they inform the writer of what their character may be thinking, feeling, or influenced by. Similarly, character designers are more effective when they tell a story with their artwork. Characters (people) aren't just random bodies with clothes slapped on them. They come from a place for reasons and have reasons for where they're going. These reasons should manifest in how they dress and how they act in an environment.

When building levels for video games, each element you have available and how you can use these elements defines your design space (range of possibilities). In Mario, the position of an element matters; the open space around it matters; the elements that come before and after it matters. You can change the size, type, and function of enemies, coins, and other elements. These variables are your knobs and switches you need to manipulate as a designer.

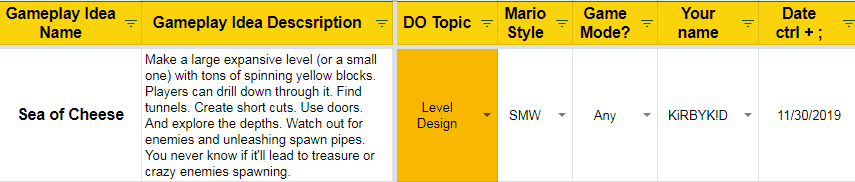

When arranging level elements to convey a gameplay idea, it helps to also have the idea broken down into smaller parts. The gameplay idea "Sea of Cheese" breaks down into many conceptual elements. Large areas of yellow spinning blocks from Super Mario World. Tunnels, Door passage ways. Unblocking enemy spawn pipes. Treasure hunting. Finding secrets. The further down you drill an abstract idea into simple, concrete elements, the easier it is to find the appropriate gameplay element that will convey it. This is how to turn a vague abstract idea into something concrete.

Different Types of Development

- One-Offs: Just like the name sounds, one-off ideas are a series of gameplay challenges, the ideas of which are conceptually unrelated. One room may feature trampolines while the other has donut blocks. Being able to platform through these challenges doesn't link the ideas on a conceptual level (or any advanced, cogent, thematically universal ideas).

- Standard Development: Taking an idea and increasing or decreasing the complexity/challenge without adding or removing any particular type of element is the most common and therefore standard way to develop a gameplay idea. e.g. 1 Goomba. 2 Goomba. 3 Goomba. 4.

- Practice Then Performance: In order to properly set the player in the right mental state or to teach them of important aspects of the game, it is common to create a practice area to precede the actual challenge. Without the tutorial section the gameplay idea would still be expressed completely by the main challenge. The tutorial almost entirely acts to set the player up for success making the whole play experience smoother.

- Explorative Development: More advanced gameplay ideas can be broken down into individual smaller concepts or facets. If the gameplay idea has its own narrative, some of the facets would be the actions that further that narrative. For example, a gameplay idea where you knock something off a tall structure and race to the floor to catch it has 3 clear actions; knock off, race, and catch. Each of these facets can be developed by using the same elements or echoing the actions in other parts of the level. What' keeps this from being a collection of separate one-offs is there must be a challenge (usually the climax) that combines all the facets back together into one challenge.

- Theme and Variation: Manipulating the elements/variables of a gameplay challenge so that the gameplay idea is similar in structure (likely due to a common facet or stressed element) but different in other significant ways (elements or facets are removed or introduced to create a distinctly new effect).

- Twist: A variation of a theme/pattern that breaks the trend to create a bigger contrast. The twist can come from an unstressed or unexplored facet of the gameplay idea. Or it can come from introducing a new element. It can be an exaggeration of a challenge or the threat of one.